If Lady Elliot were a real lady, I’d imagine that the island is her elegant head made up of octopus bushes and birds nestling in casuarina trees, surrounded by ribbons of reef to make up her sparkling aqua blue bonnet.

She emerged out of the sea as a baby coral cay about 1500 BC, but wasn’t named until a 19th century ship named Lady Elliot first recorded a sighting of this little gem located about 85 kilometres from Bundaberg. This refined little lady of the sea belongs to the Capricorn and Bunker group of reefs.

Under the watch of Lady Elliot, I feel safe from the changing world.

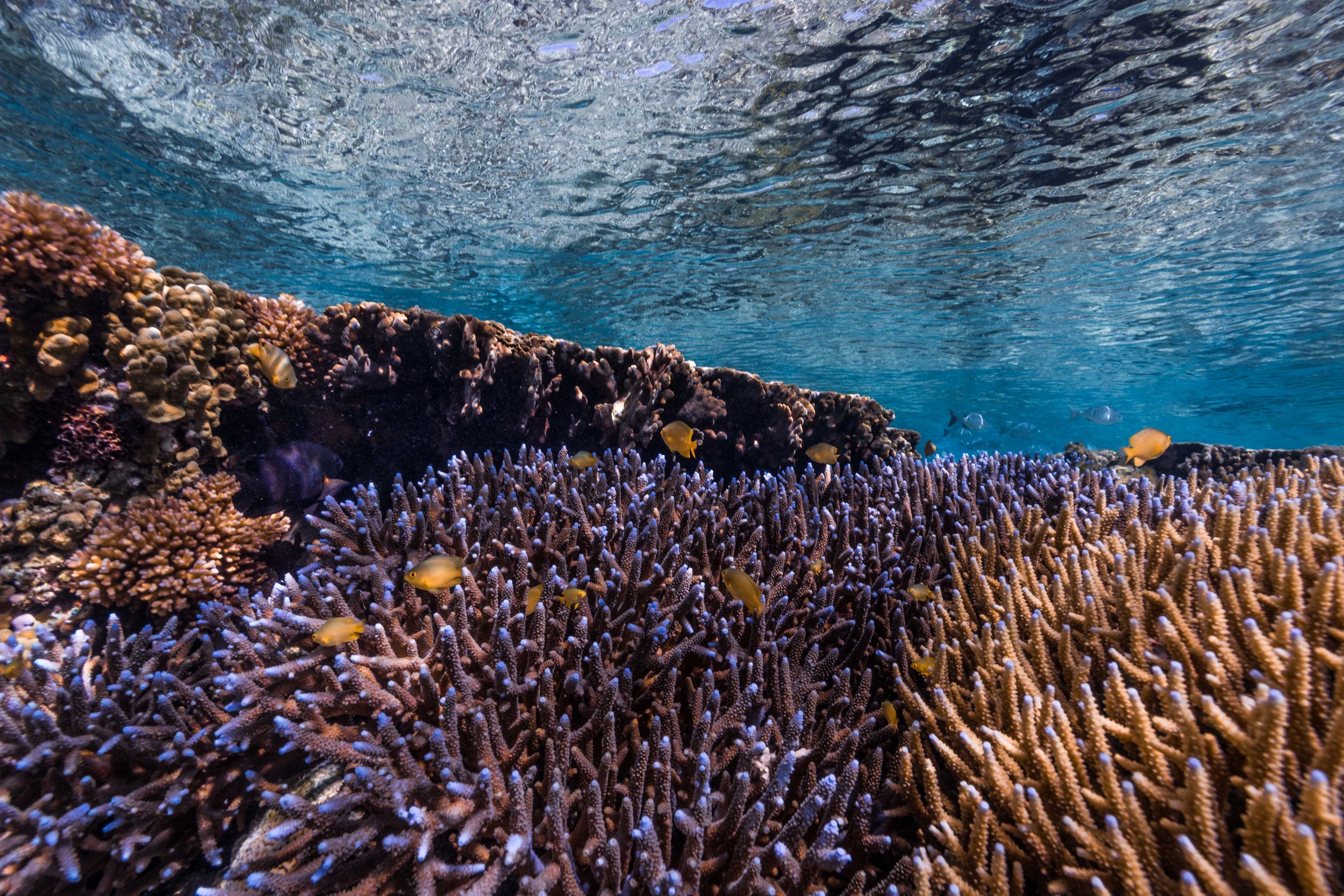

I can swim through her locks of golden and tanned pink corals without swimming into a floating pool of plastic. I can see reef sharks cruising over coral ledges and darting under coral overhangs - a good sign, as sharks are a key indicator of a healthy reef. The Great Barrier Reef’s prized eating fish, the coral trout, is also abundant in size and number, sheltering under her embrace, swimming freely around her without fear that they will be hunted down by humans.

On the south side of the island, we can see giant plates of coral on a gentle slope, as if planted there symmetrically by a gardener. (Our view of the reef is consistent with the AIMS’s report on the health of reefs in the Capricorn & Bunker group, which says the hard coral cover is relatively stable with just a small amount of coral bleaching).

While Lady Elliot’s northern friends - the reefs from Mackay, Townsville, Port Douglas and beyond - are in serious trouble, she has been spared, for now.

Lady Elliot is fortunate also because of where she is positioned.

The sweeping ribbons of reef that make her so attractive have imbued her with a great fortune - her eternal beauty has been rewarded with the greatest prize Nature can receive from any government. She has been protected from the exploits of humans.

No mining, trawling, any kind of fishing or exploitation can occur and upset this lady’s natural beauty. Although humans once denuded her of trees and shrubs so they could mine her for the excrements of seabirds, her fortune has changed.

Lady Elliot and the surrounding Capricorn and Bunker group of reefs, shoals, sea beds, and land above and below the sea, were selected long ago for consideration to become the first part of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park on the 2nd February 1977, a couple of years after the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act was established to stop limestone mining on the largest living organism on the planet.

“Under the watch of Lady Elliot, I feel safe from the changing world.”

- Danielle Ryan, Co-Director, The Map to Paradise

Lady Elliot could be the perfect Universe Model of protected reefs, the perfect representation of Mother Nature. The way we (humans) have treated her. The way she has shown resilience in recovering her natural charms and still takes care of us, despite all we have done. She is both remarkable and beautiful too.

As one of the first places to enjoy protection in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, it makes swimming around her regenerated tree-lined shores that much more special. She is nestled inside what policymakers have decided to call a ‘green zone’, meaning that everything in her reach must be left wild, untouched.

There are a few words policymakers use to categorise wild places protected by law. Here, on the Great Barrier Reef, they call them ‘green zones’, but the most universally used term is ‘marine sanctuary’.

‘Sanctuary’ is an unambiguous, appropriate choice of words, as it has a deep historical meaning. By definition, a sanctuary is a holy place, a place of refuge where everything inside remains protected from the hostilities of the world.

However, as harmonious, peaceful and poetic as the word ‘sanctuary’ sounds, as the quest to protect the sea becomes more prominent on the world stage, policymakers continue to tinker with their glossaries of terms, creating variations of what it means to truly protect Mother Nature - to create spaces of ‘sanctuary’ for her.

For this reason, it is important to remember Lady Elliot and her refined form, with her pure ribbon-reefed aqua blue bonnet, peacefully enjoying this space of ‘sanctuary.’

Remember what she looks like. Remember what the word ‘sanctuary’ means.

It is not the title ‘Great Barrier Reef Marine Park’ itself that provides protection to the reefs and wildlife that swim within it.

It is the wordy fine print beneath this name, established by lawmakers, that says what we can and cannot do to Lady Elliot and her reefy friends.

The lingo of a policy document may seem less beautiful than Lady Elliot herself, but it is the dry terminology within it that can determine her fate and whether her beauty will remain as eternal as poetry or as temporal as the lives of 90 percent of large ocean predators, which have disappeared because of overfishing - our species’ doing.

It is the power of words that rules our fate - and Lady Elliot’s fate too.

Sadly, when our eyes are distracted and we don’t pay attention to the tinkering done by human laws which attempt to govern Nature, so often we wake up only to discover that the fate of Nature has been made more uncertain.

Take another lady-named reef to the north, Marion Reef on the Coral Sea. While we weren’t looking, she has just lost half of her protection, her sanctuary. Half of her is exposed. Only half of her reefy-body is situated within a ‘sanctuary.’

And while conservationists may have won the fight to keep a sanctuary around one of the world’s best shark dive sites in the world, Osprey Reef, the width of the protection around this reef has dwindled to just a slither.

See the MAP designed in 2012, which originally offers a huge amount of protection for the Coral Sea & then the 2018 MAP, which shows a massive reduction in protection.

It is most confusing to think that a sanctuary can exist one day and not the next.

The state of New South Wales started this trend back in March 2013, as I mention in my blog article Protection is Forever (August 2018).

Then, in 2014, Australia’s then Prime Minister Tony Abbott launched a review of the proposed network of marine reserves for Australia, which lead to this year’s announcement of the largest removal of conservation areas on the planet.

So it seems that political support for Elegant Lady Elliot and all of those marine sanctuaries like her has wained, including for her sisters of the south on the east coast with their golden locks of kelp-like hair. They are more vulnerable than ever.

Most recently, in this month of September 2018, the NSW Government announced that it would no longer support the idea of creating new areas left untouched by humans, if a marine park for Sydney were created. And, now, recreational fishing interests are lobbying to open up all of New South Wales’s marine sanctuaries located in marine parks to fishing.

“A recent study shows that exploited fish populations in Australia have declined by an average of 33% between 2005 and 2015,”

- Australian Marine Science Association, 26 September 2018.

In this age of the ‘paper park’, an area that appears to protect nature only on paper, we need to start asking what does a marine park even mean anymore? Is it meaningful to say a patch of ocean is protected in a marine park, if a company can obtain a permit to mine or trawl destructively through it?

It’s not just fishing interests that are being so generously accommodated for in Australia’s marine parks, it is also confusing to think mining could be permitted within some areas of Australia’s ‘so-called’ Marine Park.

Deceivingly, it is one common nondescript letter of the alphabet that sneakily permits mining and exploration in some spaces of Australia’s Marine Park, with authorisation from the government. See the zoning and rules for Australia’s Marine Park for the Northern Territory and the north of Queensland). The letter ‘A’ has been turned into one of those symbols which determine what destruction can and cannot be done. ‘A’ is for ‘authorisation required. Activity is allowable. Subject to assessment.’

‘A’ is for an ‘alarming’ crack in the evolution of policy to protect the sea.

As the attraction to exploit marine resources grows and fishing pressure intensifies, many of these blue wild areas will change. Indeed, scientists have found that exploited fish stocks have declined by about 33% between 2012 and 2015, as referenced in this letter (September 2018) by the Australian Marine Science Association addressed to the New South Wales Government.

To save Australia’s fragile natural wonders (and all salty habitats ranging from kelp, rocky shelves, sandy bottom floors and ice), we need to assess our country’s entire waters, just as every country in the world should do, and all countries should do as they come together to negotiate a treaty to protect the high seas.

This dream seems a long way off, but we have to dream. It seems so long ago that Australians stood up and fought to protect the Great Barrier Reef from mining and, when we protected it, we believed the dream of protection was forever.

While I was not born yet to witness this achievement, today I know that we must fight again to revive that Australian dream of keeping precious areas wild and pristine.

The maps of the sea are there for all of us to explore and question. All of us must keep a watchful eye on those places we care for. It is easy to tinker with the meaning of bureaucratic words like ‘marine protected area’, a ‘marine reserve’, a ‘marine park’, a ‘special purpose zone’, but none of these words relate to true value unless we have genuine rules that do as they appear to do by name.

Names matter. Words matter. They insinuate and symbolise things. They can form and shape history. They transmit messages and meaning to our brains: when you hear of a reef named Marion or a coral cay named Lady Elliot, I think there is an assumption that someone must have thought that this place was beautiful and unique enough to protect it.

Let elegant Lady Elliot be the perfect model that we remember, when it comes to advocating for more sanctuary zones.

HISTORICAL TIMELINE:

November 2012 - Australia was still a world leader in ocean conservation. Former Federal Environment Minister Tony Burke announced a marine reserve network for Australia’s national waters, which would have made it the largest network in the world.

March 2013 - Australia takes its first major backward step on protecting the sea: the NSW State Government announced a ‘fishing amnesty’, allowing fishing inside 30 marine sanctuaries in State waters. The announcement is welcomed by fishing groups.

December 2013 - the incumbent Federal Government follows in the state of NSW’s footsteps, announcing that it would create a new plan to manage the ocean and doesn’t support ‘locking out’ fishermen from the sea. The review is launched in the following year.

March 2018 - The Federal Government starts winding back protections to the sea, making it the largest removal of conservation ever in the world.

June 2018 - the NSW Government officially reduced the extent of marine sanctuary in NSW by about a half (reducing 87 kilometres of protected coastline to just 43 kilometres), according to the Nature Conservation Council.

August 2018 - a marine park for Sydney is announced, spanning the northern region (Central Coast) and southern region (Wollongong) of Sydney. However, only 2.4 percent (48.27 square kilometres) of the total Hawkesbury Shelf Marine Bioregion (of almost 200 square kilometres) was proposed sanctuary area, making this a ‘paper park’, as very little was really protected.

September 2018 - less than a month after the NSW Government announced a marine park for Sydney, it backflipped on its support, saying it would no longer support the idea of creating marine sanctuaries inside the park, if it were created. After this announcement, recreational fishing interests announced that they would lobby further to open up all of New South Wales’s marine sanctuaries located in marine parks to fishing. Meanwhile, the Australian Marine Science Association warns in a letter to the Government that exploited fishing stocks have reduced by about 33 percent in Australia’s waters between 2012 and 2015.